- Home

- Juan Gómez Bárcena

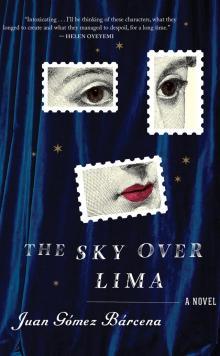

The Sky Over Lima Page 5

The Sky Over Lima Read online

Page 5

“I don’t know about you, but I think I’d rather have a muse. Or just live a long life as a bad poet.”

They both laugh.

“Maybe so.”

For a few moments neither of them says anything. The sun is now high in the sky. The birds are still singing up on the roof of the university, but the young men are hearing them only now. Soon their classmates will come out into the courtyard, shaking off the torpor of the canon law class, all mechanical and gray, like the bureaucrats they will one day become. It’s time to go home.

“If only we could invent our own biographies,” says José with something like a sigh as they get up.

“At least we can invent Juan Ramón’s,” replies Carlos, and he finishes the rest of the sentence in his thoughts.

◊

If the idea has a single origin, it is here. And if it has a single creator, then that creator is Carlos alone, however much Gálvez tries to make it his too, gathering their friends together to declare, “Gentlemen, Carlota and I have started writing a novel.” Because the truth is that everything begins with something Carlos said, and at first all José did was shake his head in silent rejection.

The conversation could take place anywhere. Perhaps on that bench in the university courtyard, or maybe on the rooftop that always seems on the verge of collapsing, or in a tavern where they’re drunkenly passing the time till last call with bureaucratic patience. Carlos, uncharacteristically, speaks. The night before, demoralized once again by the rejection of one of his poems by yet another magazine, José has suggested that perhaps the time has come to forget about their correspondence with Juan Ramón. After all, what has their wearisome prank produced but a bunch of headaches, a few signed sheets of paper, and the nickname, however amusing it might be, of Carlota? They’re never going to become better poets like this, much less find a muse who will get them there. And so: To hell with Georgina. But Carlos doesn’t agree. For the first time, he refrains from answering with one of the expressions he’s rehearsed in his mirror and instead responds with a No that arises from deep within him. Definitively: No. His voice trembles, because he is, after all, only a rubber man’s son, made to accommodate all José’s desires, but even so he does not give in. No, he repeats stubbornly. Why not? Carlos can’t really explain. No, I said no. And that’s that.

He can’t sleep that night. Lying in bed, he mulls over what José said about muses. Just before he falls asleep, he thinks he has found the answer. An argument that, knowing his friend, will absolutely convince him. One that could change the direction of their lives. And so when they meet up again at last, he gives the speech he’s prepared for the occasion. A stammering monologue that Gálvez listens to in silence. Or at least he does for a few minutes, with a condescension that might be mistaken for respect. But at a certain point he can’t take any more and impatiently breaks in.

“No, no, no, what are you saying, Carlitos, what novel? Stop talking nonsense! We don’t write novels, remember? We leave that to Sandoval and his crowd.”

José doesn’t understand. Or maybe he doesn’t understand what his friend is doing having an idea of his own, regardless of what it is. So Carlos has to insist, despite how difficult it is for him to contradict José, despite how often he touches his hair or nervously clears his throat as he speaks. He asks José if he remembers when they said that everyone’s lives were literature, and José replies simply, “Yes.” Those afternoons up on the roof, when the world seemed to them to be full of secondary characters and only a handful of protagonists? And José answers, “Of course.” Those discussions in which they decided what writer was writing the life of each person? And José squawks, “I said yes, damn it.” Well, th-this, stutters Carlos, is exactly the same thing. The life of Juan Ramón is a novel too, and chapter by chapter, letter by letter, they have already begun to write it, though they hadn’t realized it until now. All this time, they thought they were playing a fairly tiresome prank or collecting a few souvenirs, but what they were really doing was something much more serious: writing the novel of the life of a genius.

José opens his mouth. Then closes it. And Carlos goes on, stammering less and less. Because while it may be that they don’t have their own muse and so will never manage to produce a perfect poem, he adds, in the end, what does that matter? Perhaps providence has reserved for them, Carlos Rodríguez and José Gálvez Barrenechea, a far nobler fate: out of nothing, creating the beauty celebrated by another poet. And who knows, continues Carlos, who can no longer stop himself, maybe that’s another sort of perfect poem, the only one that is truly transcendent, molding the clay of words and saying to them: Rise, and go forth. The two of them would resemble God the Father and Creator of all things, were it not a sin to say so, or even think it. They are giving life to the muse with whom Juan Ramón must fall in love, and that story, that tempestuous romance, that fragment of life caught midway between reality and fiction, will be their novel. And if one day the Maestro builds a poem upon the embers of that love, even just one, they will know in their hearts that they’ve done the most difficult thing of all: that they couldn’t be more responsible for the beauty of that poem if they’d written it themselves.

Carlos stops. To bolster his thesis that everything is literature, that the entire world is a text constructed of words alone, he would like to cite Foucault, Lacan, Derrida. But he cannot, because Derrida and Lacan and Foucault have not yet been born. Actually, Lacan has: he is three years old and currently playing with a jigsaw puzzle—it’s morning in Paris—perhaps constructing future memories of what he will one day call the mirror stage. So Carlos has nothing else to add.

José doesn’t either. Instead he stares, as if his friend had only just now begun to exist.

He agrees with a slow nod.

He smiles the same smile with which he celebrated Georgina’s birth.

II

A Love Story

◊

Their novel does not yet have a title or a defined plot. All they know are the names of the two protagonists and the settings they inhabit: a real Lima and a Madrid vaguely imagined from the other side of the Atlantic.

It starts out as a comedy. Or at least it seems that way. The opening pages are full of rich men pretending to be poor and men pretending to be women and squatting down to urinate in empty avenues. There are mistakes and laughter and gluttonous rats that nest in mail sacks; there are bottles of pisco and chicha. A great poet is tricked as if he were a child, and two children pretend to be great poets. There is envy, too, but the kind that is ultimately healthy, bracing, not bitter, as well as a trend among Lima’s wealthy youth to write to their favorite authors pretending to be infatuated young ladies.

Perhaps in keeping with this jovial spirit, the letters between Georgina and Juan Ramón are also breezy and light, like notes passed between schoolchildren. For José and Carlos, the authors of the comedy, it is a happy period, partly because they enjoy the writing and partly because they feel like protagonists in their own novel. Telling them otherwise, informing them that Georgina is the sole protagonist, would likely be a fruitless endeavor. They are young, full of ambition and dreams; they are still unable to imagine that there might be a story in the world in which they are not the main characters.

Then comes the revelation. They discover they’ve been mistaken all along. It is not a comedy. It never has been, even if the drunken revels and the hoaxes and the little blind girls writing to Yeats made them believe otherwise. It is a love story, perfectly in keeping with so many other beautiful books before it, and only they can write it. An epistolary novel on a par with Goethe’s Werther and Richardson’s Pamela—maybe even better than those, as theirs will be the first book in history to be inhabited by flesh-and-blood characters. Each letter sent or received constitutes a chapter of the novel. Juan Ramón, Georgina, the friends and relatives to which the two of them refer—they are all characters brought to life in these pages. The poem that the Maestro will one day write to his beloved is

the perfect dénouement. And Carlos and José are the authors, of course, clever novelists who shut themselves away in the garret to deliberate over the details of the plot. They say, for example: “The heroine becomes somewhat overwrought in the fifth chapter; we should bring down the tension a bit in the seventh.” Or perhaps: “Would you take another look at the latest chapter? I’ve noticed a plausibility problem in the first paragraph.”

It’s true, it still feels like a game. In a way, though, it’s the most serious thing they’ve ever done.

Of course, between letters, many things happen. After all, a ship takes no less than thirty days to cross the Atlantic. Everything is slow in 1904, from the length of a mourning period to the time needed to pose for a photograph. And so during the long spells of waiting, José and Carlos’s life continues: their mornings playing hooky, their afternoons lounging in the garret, and their nights carousing at the club; their evenings attending plays and concerts; their afternoons sunbathing and swimming in the sea at Chorrillos; their Saturdays placing bets at the cockfighting ring in Huanquilla or at the Santa Beatriz racetrack or at the billiards tables; their Sundays enduring Mass and watching the hours tick by on the sitting-room clock; their ends of semesters forging grade reports; their spring afternoons strolling up and down Jirón de la Unión; their first and third Wednesdays of every month making and receiving visits, drinking hot chocolate and eating cookies, bowing and listening to piano recitals, discussing the weather or the advantages of train travel with prim young ladies who may one day be their wives. All of that is what they used to call life, but now it seems like only a slow and sticky dream, exasperating in the way it passes drop by suffocating drop. As if the whole world has gone mad and only their letters can keep it going. Real life now consists of waiting for the transatlantic steamship to dock in El Callao and unload its supply of letters from the Maestro. Sitting in the club talking about their flesh-and-blood novel and watching the other patrons gradually lose interest in Sandoval’s dockworkers’ strike, which never quite takes off. Writing the next letter.

To improve their efforts, they consult a book entitled Advice for a Young Novelist, a seven-hundred-page tome that is rather short on advice and long on commandments and whose target audience seems to be not a young writer but an elderly scholar. The author, one Johannes Schneider, repeatedly employs the words dissection, exhumation, analysis, and autopsy. One could not ask for greater honesty, as indeed the book undertakes with Prussian rigor the task of dismembering World Literature, until everything extraordinary and beautiful in that genre is writhing under its scalpel. The boys take turns reading it aloud, but they always end up dozing off, unable to make it past the one hundred and fourteenth guideline. One inspired night, they decide to light the wood stove in the garret with its pages, timidly at first, but when they see it blaze up they can no longer hold back. Laughing wildly, they burn the seven hundred guidelines, page by page, in a celebration reminiscent of a pagan ritual, of a liberation from the old and the advent of the unknown: a new literature that will have no pages with which to warm oneself, only events and endeavors that will make their mark on the flesh and memory of men. They contemplate this as the flames waver and tremble, and their laughter gradually dies out with them; somewhere the cat scampers and howls, and downstairs the Chinese tenants eat or dream or sing old songs about the Yellow River, or simply continue the business of living without thinking about anything, attempting to remain unaware that they are already starting to forget the faces of their mothers and wives.

◊

Perhaps it is too much to call them writers just because they’ve authored a few letters. It depends on how much importance we grant their correspondence, not to mention how seriously we take the craft of writing itself, which is not really a profession but something closer to an act of faith. The only thing we can know for sure is this: They believe they are writers. And just as with a hysterical pregnancy, when the body swells to harbor a child that will never be born, their position as hypothetical literary figures brings with it some of the same virtues and defects exhibited by actual writers.

And so it is that their first insecurities and fears arise, the welter of anxieties that every creator must inevitably encounter sooner or later. In the end, no author who isn’t an idiot—though we mustn’t discount the possibility that a good writer may be one—can blindly trust in something so fragile as words, which after all are the raw material of his work. And so both of them are afraid, but, as no two artists are entirely alike, their fears are quite different.

José fears, among other things, that Juan Ramón will find them out and stop writing letters; that Juan Ramón will not find out but even so will stop writing letters; that the men at the club would rather talk about Sandoval’s strike than about their novel; that the Maestro is already engaged, or has a muse, or both; that though he and Carlos believe they are writing a set of letters on the level of Ovid’s Heroides, in fact their work is fit only for a tawdry melodrama. Most of all, though, he is afraid that Juan Ramón will never write the poem for Georgina—or, worse still, that he will write it and it will be mediocre. To be frank, he is afraid the poem will be awful, a monstrosity, a literary abomination, and that, what’s more, the ingrate will dedicate it to her; what good will it do to have authored a muse who inspires not ardent passions but wretched little verses dictated by piety, or boredom, or even friendship, which is what men always seem to talk about when they’re really talking about women for whom they feel nothing?

Carlos, for his part, is not worried about the as-yet-unwritten poem. His fears are, in fact, just one alone: That Georgina will not be good enough. That after all the letters, after imagining her for so many sleepless nights, they will have managed to produce only a vulgar, insignificant woman, a woman incapable of piquing Juan Ramón’s interest. That she is condemned forever to be a secondary character, one of the countless nondescript women they see pass by from their perch above the garret, nameless, pointless. Where are they going, and why would anyone care? His doubts are reinforced every time they receive a letter that is a little more ceremonious, a little stiffer than usual. How do they know Juan Ramón isn’t writing a hundred letters just like these every day? One morning Carlos reads an article in the paper about the assembly lines that automobile manufacturers are starting to use in the United States, and that night he dreams about Juan Ramón sitting in his study, feverishly occupied in assembling polite clichés, sealing envelopes, and tweaking paragraphs that are repeated in identical form in letter after letter.

. . . This morning I received your letter, which I found most charming, and I am sending you my book at once, regretting only that my verses cannot live up to all that you must have hoped they would be, Georgina/María/Magdalena/Francisca/Carlota . . .

This is the core of his fear, if fear can have precise contours: that his Georgina will end up meaning more to him than she does to the Maestro.

◊

It doesn’t matter who tells them about the scriveners in the Plaza de Santo Domingo. Whoever it is, in any case, quickly convinces them that it’s the only place for them to go for help writing their novel. And that Professor Cristóbal, an expert in lovers’ notes and epistolary courtship, is just the person they need.

If José and Carlos had seen the Professor pass by from their garret, with his shabby hat and his scribbler’s gear on his back, they would have quickly declared him a secondary character. And they would have been right, at least as far as this story is concerned. But if daily life in Lima in 1904 had its own novel, let’s say a volume of some four hundred pages, then Professor Cristóbal would certainly deserve a protagonist’s role, if only for the secrets that have passed through his hands over the course of two decades. Not even all the priests in the city, compiling all the innumerable tales they’ve heard in their confessionals, could attain a clearer picture of their parishioners’ consciences.

The lives of illustrious men begin with their birth and, in a sense, even earlier, with

the feats of the ancestors who bestow upon them their last names and titles. Humble men, however, come into the world much later, once they have hands that are able to work and backs able to bear a certain amount of weight. Some—most—are never born at all. They remain invisible their whole lives, dwelling in miserable corners where History does not linger. You could say that Cristóbal was born at seventeen, when he was given a lowly position in a Lima notary office. All that preceded that moment—his childhood, his longings, the reasons for his indigent family’s extraordinary determination to provide him with proper lessons in reading and writing—is a mystery. Or, rather, it would be a mystery if anyone took an interest in finding it out. But no one does; nobody cares. And so his biography begins there, in a dingy room piled with papers where the notary ordered him to steam codicils open and keep certain bits of money apart from the rest of the accounting. Like any newborn, Cristóbal obeyed in silence, not questioning the world around him. We know as little about what passed through his head during this period as we do about what took place before his birth.

In 1879 Professor Cristóbal was called to the front to serve as an infantryman in Arauca during the disastrous war against Chile. At the time, of course, he hadn’t yet acquired his nickname. And the war against the Chileans still seemed less like a catastrophe and more like a sporting event or a hunting party, a long pilgrimage made so that the young men could wear trim uniforms with epaulets and have their cries of Long live this and Down with that ring out across the countryside. With the first shots fired came a number of bitter revelations. After a couple of days of combat, the uniforms were soiled with mire and blood, and the young men no longer seemed so young, and it was those newly fledged men, not ideas or nations, who began to die in the dusty ditches. Many of them were no doubt still virgins, which for some reason Cristóbal found saddest of all. That and the fact that his illiterate comrades, which was most of them, didn’t even have the consolation of reading their loved ones’ letters before they died. One day, upon hearing the dying wishes of a brother-in-arms, Cristóbal agreed to take dictation as the young man bade his mother farewell. On another occasion he helped his sergeant craft a marriage proposal to his wartime pen pal, and before he knew it he was earning his service pay writing the private correspondence of half the company. He was even made Captain Hornos’s personal assistant, a promotion that had a good deal to do with the six sweethearts the captain had left behind in Lima, women who required daily appeasement with promises and poetry.

The Sky Over Lima

The Sky Over Lima